Difference between revisions of "Systems Analysis & Design"

Adelo Vieira (talk | contribs) (→Requirements elicitation) |

Adelo Vieira (talk | contribs) (→Interviews) |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

=====Interviews===== | =====Interviews===== | ||

Successful elicitation of requirements depends on good communication with clients and users, and one of the most effective ways of achieving good communication is through one-toone interviews. Ideally, a developer should interview everyone in the client organization, from secretaries and office juniors to bosses and managers. However, in a large business this is clearly not practicable, so it is important that those members of staff who are interviewed are a representative cross-section of the people who will be involved in the new system. In the case of the Wheels system development project, the developer should interview at least the owner of the business, the shop manager and one of the mechanics. The opinions of Wheels' customers should also be canvassed, but it is more appropriate to do this using a questionnaire. | Successful elicitation of requirements depends on good communication with clients and users, and one of the most effective ways of achieving good communication is through one-toone interviews. Ideally, a developer should interview everyone in the client organization, from secretaries and office juniors to bosses and managers. However, in a large business this is clearly not practicable, so it is important that those members of staff who are interviewed are a representative cross-section of the people who will be involved in the new system. In the case of the Wheels system development project, the developer should interview at least the owner of the business, the shop manager and one of the mechanics. The opinions of Wheels' customers should also be canvassed, but it is more appropriate to do this using a questionnaire. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In order to gather as much relevant information as possible, the interview must be well prepared. It is useful to produce a plan that is given to the interviewee in advance, stating the time and place of the interview, the kind of topics that will be covered and any documents that the interviewee should bring along. The following figure shows the plan for an interview with Annie Price, the shop manager at Wheels. The interviewer is Simon Davis, a system developer on the Wheels project. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Interview_plan.png|650px|thumb|center|Interview plan]] | ||

===UML=== | ===UML=== | ||

Revision as of 21:44, 16 March 2018

Contents

- 1 UML/CASE tools

- 2 Xtra-vision express URL (Importante: revisar esto para la próxima clase)

- 3 A student guide to object-oriented development

UML/CASE tools

UML/CASE tools such as: Visual Paradigm, Dia, ARGO or Draw.io

Visual Paradigm

Software required for this course: Visual Paradigm (Community Edition) You must register but it is a free trial version

Link to Visual Pardigm community edition (free): http://www.visual-paradigm.com/download/community.jsp

Visual Paradigm User's Guide: https://www.visual-paradigm.com/support/documents/vpuserguide.jsp

Xtra-vision express URL (Importante: revisar esto para la próxima clase)

Click https://xtra-vision.ie/how-it-works/ link to open resource.

A student guide to object-oriented development

En este curso nos vamos a baser en este libro: «A student guide to object-oriented development». The book describes how a software system is developed using an object-oriented approach. Para esto, el libro describe el caso de un small business, «the Wheels bike hire company».

The Wheels bike hire company: The case study which is used as the basis for examples and exercises in this book is a typical bicycle hire shop.

Como mencionamos, the approach used is object-orientation, which means that the whole development process is based round the object - a thing or concept that initially represents something in the real world and eventually ends up as a component of the system code. An object-oriented system is made up of objects that collaborate to achieve the required functionality, what the system has to do.

There are two websites for the book, which can be found at:

- One for students: http://books.elsevier.com/companions/o75o661232

- And one for lecturers: http://books.elsevier.com/manualsprotected/0750661232

These sites contain further models for the second case study, a complete set of lecture slides, electronic copy of the code and multiple choice questions for topics covered in the book. There is also a revision notes section that will be helpful as an aide-m6moire for students who are studying for exams.

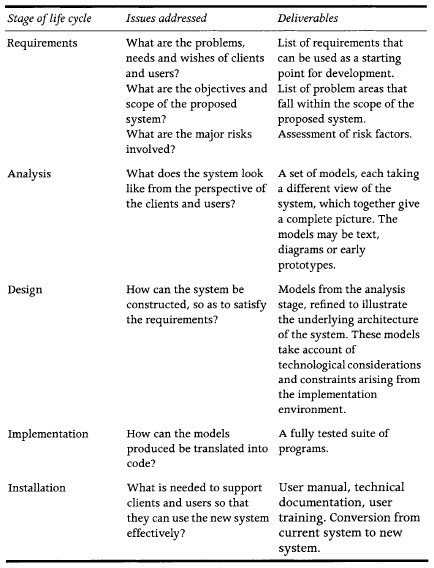

The traditional system life cycle

When undertaking any large project, it is important to have some kind of framework in order to help identify milestones, structure activities and monitor deliverables.

A life cycle provides a high-level representation of the stages that a development project must go through to produce a successful system.

In software system development, a framework has traditionally been known as a system life cycle model. Although life cycle models have been around for a long time, there is still no general agreement about the precise stages in the development process, the activities that take place at any particular stage, or what is produced at the end of it. This is hardly surprising, since factors such as the type of system being built, the software being used, the timescales and the development environment will all influence decisions about the detailed stages of a project.

However, at a higher level, there is agreement that there are certain life cycle stages that all projects must go through in order to reach a successful completion. Historically these stages have been referred to as:

- Requirements,

- Analysis,

- Design,

- Implementation

- Installation.

Each stage is concerned with particular issues and produces a set of outputs or deliverables:

Traditional life cycle models

Over the years there have been a number of life cycle models based on the development stages outlined in Table 1.2. In this section we briefly introduce some of the most widely used models:

- Waterfall.

- V-model.

- Spiral.

- Prototyping.

- Iterative development.

- Incremental development.

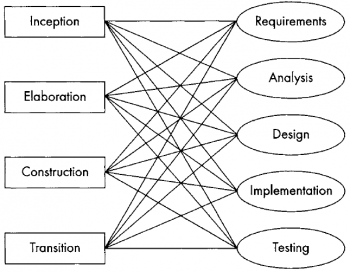

The object-oriented approach

One of the differences that is immediately obvious between traditional life cycle models and the object-oriented approach is the way that the various stages are named. In traditional models the names, such as 'analysis' or 'implementation', reflect the activities that are intended to be carried out in that stage. In object orientation, however, a clear distinction is made between the activities and the stages (generally referred to as phases) of development. The phases in object-oriented development are known as inception, elaboration, construction and transition, indicating the state of the system, rather than what happens at that point in development.

- Inception: it covers the initial work required to set up and agree terms for the project. It includes establishing the business case for the project, incorporating basic risk assessment and the scope of the system that is to be developed.

- Elaboration: it deals with putting the basic architecture of the system in place and agreeing a plan for construction. During this phase a design is produced that shows that the system can be developed within the agreed constraints of time and cost.

- Construction: it involves a series of iterations covering the bulk of the work on building the system; it ends with the beta release of the system, which means that it still has to undergo rigorous testing.

- Transition: covers the processes involved in transferring the system to the clients and users. This includes sorting out errors and problems that have arisen during the development process.

Instead of the traditional high-level system life cycle, the object-oriented approach to development views the relationships between workflows and phases of development rather like the spider's web in the following figure, where any phase may involve all workflows, and a workflow may be carried out during any phase.

The Rational Unified Process (RUP)

A life cycle provides a high-level representation of the stages that a development project must go through to produce a successful system, but it does not attempt to dictate how this should be achieved, nor does it describe the activities that should be carried out at each stage. A development method, on the other hand, is much more prescriptive, often setting down in detail the tasks, responsibilities, processes, prerequisites, deliverables and milestones for each stage of the project.

Over the past decade, there have been a number of object-oriented development methods, such as Responsibility-Driven Design (Wirfs-Brock et al., 199o ), Object Modelling Technique (Rumbaugh et al., 1991) and Open (Graham et al., 1998 ).

Nowadays, almost all object-oriented projects use the Unified Modelling Language as the principal tool in their development process. Use of the UML has been approved by the Object Management Group (OMG), which controls issues of standardization in this area. However, UML is simply a notation or language for development; it is not in itself a development method and does not include detailed instructions on how it should be used in a project.

The creators of the UML, Ivar Jacobson, Grady Booch and James Rumbaugh, have proposed a generic object-oriented development method in their book The Unified Software Development Process (Jacobson et al., 1999) and this generic method has been adopted and marketed by the Rational Corporation under the name of the Rational Unified Process (RUP). RUP incorporates not only modelling techniques from the UML, but also guidelines, templates and tools to ensure effective and successful development of software systems. The tools offered by RUP allow a large part of the development process to be automated, including modelling, programming, testing, managing the project and managing change.

RUP is based on the following six 'Best Practices' which have been formulated from experience on many industrial software projects:

- Develop software iteratively

- Manage requirements

- Use component-based architectures

- Visually model software

- Verify software quality

- Control changes to software.

RUP is an increasingly popular approach to developing software systems, and is already laying claim to be the industry standard. However, it would be overkill to work through all the details of RUP in this book, since the book is based around the development of a small, simple information system. We therefore describe the development of the Wheels bike hire system within a simplified object-oriented framework.

Requirements for the Wheels case study system

Here we describe Wheels through techniques that are typically used early in the development process to establish how things are done at present and identify what the client wants and needs from the new system. The activities that capture and record client requirements are known collectively as requirements engineering. This is a crucial part of any system development project. We can see this most clearly by imagining what happens if we get the requirements wrong: it will not matter how well the system is designed or how elegant the code, if the system does not do what the clients and users want, it is useless.

Requirements engineering is traditionally divided into three main stages:

- Elicitation, when information is gathered relating to the existing

system, current problems and requirements for the future

- Specification, when the information that has been collected is

ordered and documented

- Validation, when the recorded requirements are checked to

ensure that they are consistent with what the clients and users actually want and need.

Requirements elicitation

During requirements elicitation, the focus is on collecting as much information as possible about what the clients and users want and need from the new system. This usually involves a large amount of work examining the way in which the system operates at present, whether it is manual, automated, or a mixture of both. Techniques for requirements elicitation include:

- interviews,

- questionnaires,

- study of documents,

- observation of people carrying out day-to-day tasks,

- assessment of the current computer system if there is one.

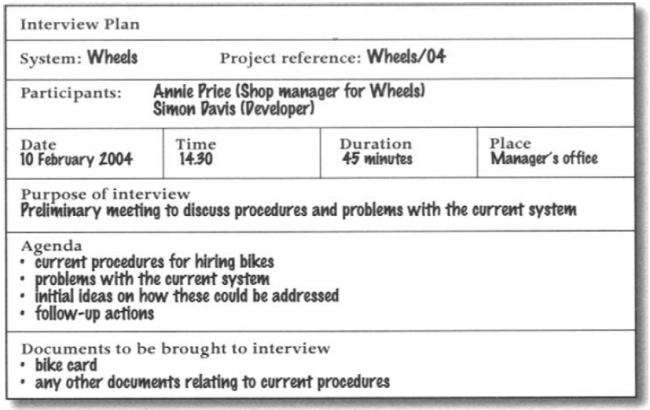

Interviews

Successful elicitation of requirements depends on good communication with clients and users, and one of the most effective ways of achieving good communication is through one-toone interviews. Ideally, a developer should interview everyone in the client organization, from secretaries and office juniors to bosses and managers. However, in a large business this is clearly not practicable, so it is important that those members of staff who are interviewed are a representative cross-section of the people who will be involved in the new system. In the case of the Wheels system development project, the developer should interview at least the owner of the business, the shop manager and one of the mechanics. The opinions of Wheels' customers should also be canvassed, but it is more appropriate to do this using a questionnaire.

In order to gather as much relevant information as possible, the interview must be well prepared. It is useful to produce a plan that is given to the interviewee in advance, stating the time and place of the interview, the kind of topics that will be covered and any documents that the interviewee should bring along. The following figure shows the plan for an interview with Annie Price, the shop manager at Wheels. The interviewer is Simon Davis, a system developer on the Wheels project.

UML

The UML (Unified Modeling Language) is an international industry standard graphical notation for describing software analysis and designs.

The Unified Mode]ling Language, or UML, is a set of diagrammatic techniques, which are specifically tailored for object-oriented development, and which have become an industry standard for modelling object-oriented systems. The UML grew out of the work of James Rumbaugh, Orady Booch and Ivor Jacobson, and has been approved as a development standard by the Object Management Group. Before discussing the UML in detail we should explain briefly what we mean by 'mode]ling' in this context, and why it is an important part of software system development.

Modelling:

Architects and engineers have always used special types of drawing to help them to describe what they are designing and building. In the same way, software developers use specialized diagrams to model the system that they are working on throughout the development process. Each model produced represents part of the system or some aspect of it, such as the structure of the stored data, or the way that operations are carried out. Each model provides a view of the system, but not the whole picture.

Fundamental UML models:

As we mentioned in the previous section, the UML is not a development method since it does not prescribe what developers should do, it is a diagrammatic language or notation, providing a set of diagramming techniques that model the system from different points of view. The following table shows the principal UML models with a brief description of what each can tell us about the developing system.

The 4 + 1 view: The authors of UML, Booch et al., (1999), suggest we look at the architecture of a system from five different perspectives or views:

- The use case view

- The design view

- The process view

- The implementation view

- The deployment view.

This is known as the 4 + 1 view (rather than the 5 views) because of the special role played by the use case view. The use case view of the system is the users' view: it specifies what the user wants the system to do; the other 4 views describe how to achieve this.

There are five fundamental UML models:

- Use case model

- Class model,

- Sequence model

- State model

- Activity diagrams

Use case model

The use case model consists of:

- A use case diagram,

- A set of use case descriptions,

- A set of actor descriptions, and

- A set of scenarios.

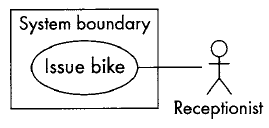

A use case diagram

The use case diagram models the problem domain graphically using four concepts:

- The use case,

- The actor,

- The relationship link, and

- The boundary.

UML symbols used to model these concepts:

- A use case: an ellipse labelled with the name of the use case. Conventionally we start each use case name with a verb to make the point that use cases represent processes. So we have 'Maintain customer list' rather than 'Customer list', 'Handle enquiries' rather than 'Enquiries'.

- An actor: a stick figure labelled with the name of the actor. We capitalize actor names so that they are easy to identify as such (e.g. Administrator, Receptionist). The stick figure icon is used even when the actor is non-human, e.g. another computer system or an organization.

- A use case relationship: a line linking an actor to a use case. The line shows us which actors are associated with which use cases. This relationship is also known as a communication association.

- The boundary: a line drawn round the use cases to separate them from the actors and to delineate the area of interest. Can be labelled to indicate the diagram domain. The boundary is often omitted.

The use cas:

What we do when identifying use cases is to divide up the system's functionality into chunks, into the main system activities. What dictates the split is what the user sees as the separate jobs or processes (the tasks he will do using the system).

Identifying use cases from the actors: There are several ways of approaching use case identification. One is to identify the actors, the users of the system, and for each one, to establish how they use the system, what they use it to achieve.

If we look at the interview in Chapter 2 we can see that Annie and Simon start off by talking about issuing bikes, one of the main jobs that make up Annie's working day. Issuing bikes therefore will be one of the use cases. Issuing bikes involves: finding a suitable bike, calculating the hire charge, collecting the money, issuing a receipt and recording details of the customer and the hire transaction.

The interview moves on to discuss dealing with the return of a bike. Annie sees this as a separate job from issuing the bike, it is separated in time and involves a different set of procedures- checking the date and the condition of the bike and returning the deposit.

Annie tells us in the interview that a list of bikes is already held on the computer, but they do not seem to be able to use it to help them in their work. The bike list needs to be stored so that it can be used to answer queries about what bikes Wheels have, whether they are available or on hire, what their deposit and hire charges are and so on. Maintaining this bike list is another use case.

Handling queries is seen by Annie as a separate job from issuing bikes. She often gets people coming into the shop or phoning just to check on the range of bikes available and get an idea of costs. This sometimes leads to a hire, but more often it does not. We can therefore identify Handle enquiries as a separate use case.

It also emerges from the interview that no record is kept of customer details or of what bikes they have hired on previous occasions. This sort of information would be useful for marketing purposes and to simplify dealing with requests for the same bike (see the Problem Definition (Figure 2.6), the Problems and Requirements List (Figure 2.7) and the Interview Summary (Figure 2.8)). Maintain customer list can therefore be identified as a use case.

Identifying use cases from scenarios: Another approach to identifying use cases is to start with the scenarios. We have already mentioned scenarios in Chapter 2 - a scenario describes a series of interactions between the user and the system in order to achieve a specified goal. A scenario describes a specific sequence of events, for example what happened when Annie successfully issued a bike to a customer.

Each use case represents a group of scenarios. Scenarios belonging to the same use case have a common goal- each scenario in the group describes a different sequence of events involved in achieving (or failing to achieve) the use case goal. A continuación, we describe scenarios belonging to the 'Issue bike' use case; in both cases Annie is trying to issue a bike to a customer.

Successful scenario for the use case Issue bike:

- Stephanie arrives at the shop at 9.ooam one Saturday and chooses a mountain bike

- Annie sees that its number is 468

- Annie enters this number into the system

- The system confirms that this is a woman~ mountain bike and displays the daily rate (s and the deposit (s

- Stephanie says she wants to hire the bike for a week

- Annie enters this and the system displays the total cost s + s = s

- Stephanie agrees this

- Annie enters Stephanie~ name, address and telephone number into the system

- Stephanie pays the s

- Annie records this on the system and the system prints out a receipt

- Stephanie agrees to bring the bike back by 9.ooam on the following Saturday.

Scenario for "Issue bike" where the use case goal is not achieved:

- Michael arrives at the shop at 12.oo on Friday

- He selects a man~ racer

- Annie see the number is 658

- She enters this number into the system

- The system confirms that it is a man's racer and displays the daily rate (€2) and the deposit (€55)

- Michael says this is too much and leaves the shop without hiring the bike.

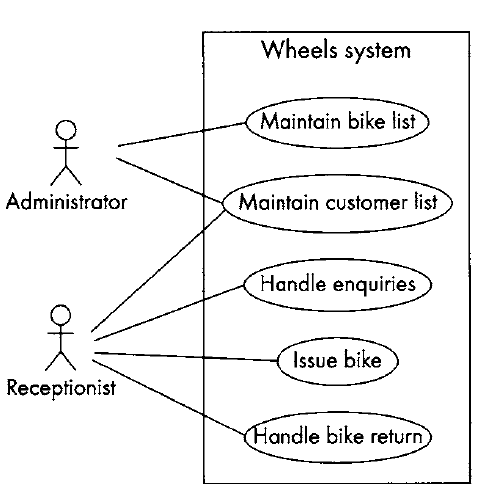

En la siguiente figura we shows a use case diagram of the Wheels case study. The functionality of the new system has been divided into five use cases: 'Maintain bike list', 'Maintain customer list', 'Handle enquiries', 'Issue bike' and 'Handle bike return'. Conceptually a use case diagram is similar to a top-level menu which lists the five main things that the system does. Each use case is linked by a line to an actor. The actor, represented by a stick figure, is the person (sometimes a computer system or an organization) who uses the system in the way specified in the use case or who benefits from the use case.

Use case descriptions

The use case description is a narrative document that describes, in general terms, the required functionality of the use case.

The class diagram

The class diagram is central to object-oriented analysis and design, it defines both the software architecture, i.e. the overall structure of the system, and the structure of every object in the system. We use it to model classes and the relationships between classes, and also to model higher-level structures comprising collections of classes grouped into packages. The class diagram appears through successive iterations at every stage in the development process. It is used first to model things in the application domain as part of requirements capture. Subsequently, with classes added which are part of the solution not the problem domain (e.g. interface classes), it is used to design a solution. Finally, with classes added to facilitate the implementation (e.g. buttons, windows, mouselisteners, etc.), it is used to design the program code.

Stages in building a class diagram

One way to approach the class diagram is by use case realization. In use case realization we look at each use case in turn and decide what classes we would need to provide the functionality modelled in the use case. The group of classes required by a use case is called a collaboration. When each use case has been analysed, the resulting collaborations are amalgamated into a unified class diagram. We will look at collaborations in Chapter 6, but for the moment we are going to use a different approach to developing the class diagram. We will develop a domain model, i.e. a class diagram that sets out to model all of the classes in the problem domain in one go, not use case by use case. Both approaches should eventually arrive at the same model.

Stages to build a class diagram (domain model):

- Identify the objects and derive classes

- Identify attributes

- Identify relationships between the classes

- Write a data dictionary to support the class diagram

- Identify class responsibilities using CRC cards

- Separate responsibilities into operations and attributes

- Write process specifications to describe the operations.

Identify the objects and derive classes:

Class diagrams are a very useful way of modelling the structure of the objects in a system and the links between them. However, when we are trying to design a new software application, we don't know what the classes are in advance and we will often start by looking for objects before making decisions about what their class will be.

Objects come in different categories; being aware of the categories gives us an idea of the sorts of things to look for. Objects at the analysis stage will be things that have meaning in the application domain. They can be:

- People (such as customers, employees, students, librarians)

- Organizations (such as companies, universities, libraries)

- Physical things (such as books, bikes, products)

- Conceptual things (such as book loans and returns, customer orders, seating plans).

Various techniques can be used for object identification, none of them are foolproof, none can be guaranteed to produce a definitive list of objects and classes; they are just guidelines that might help. A good starting point is to look at the documentation about the system produced so far and to search for nouns in any description of the system requirements, preferably one that is complete and concise.

Object identification using noun analysis:

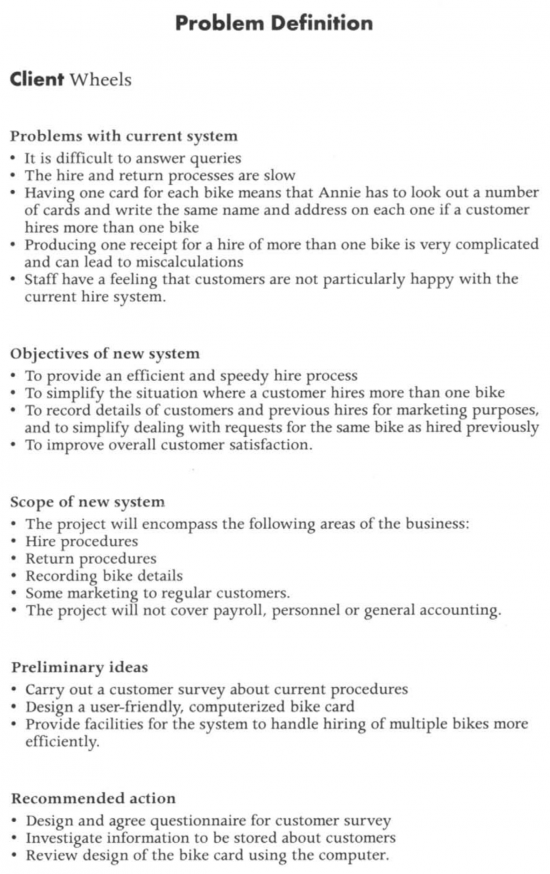

- First, find a complete but concise description of the system requirements. The Problem Definition in Figure Figure 1 (Chapter 2 del libro) is often a good place to look. Use case descriptions are also useful for this purpose, although for a complete description of the system you would have to look at all of the use case descriptions.

- Pick out all of the nouns and noun phrases and underline them. This usually provides a rather long list of possible (or candidate) objects, many of which are obviously unsuitable and some of which are unsuitable in more subtle ways.

- Reject unsuitable candidates by applying a list of rejection criteria.

For our object analysis we will use the list of requirements produced at the end of Chapter 2:

- R1: keep a complete list of all bikes and their details including bike number e typer sizer maker modelr daily charge rate, deposit; (this is already on the Wheels system)

- R2: keep a record of all customers and their past hire transactions;

- R3: work out automatically how much it will cost to hire a given bike for a given number of days

- R4: record the details of a hire transaction including the start date, estimated duration, customer and bike, in such a way that it is easy to find the relevant transaction details when a bike is returned

- R5: keep track of how many bikes a customer is hiring so that the customer gets one unified receipt not a separate one for each bike

- R6: cope with a customer who hires more than one bike, each for different amounts of time

- R7: work out automatically, on the return of a bike, how long it was hired for, how many days were originally paid for, how much extra is due

- R8: record the total amount due and how much has been paid

- R9: print a receipt for each customer

- R10: keep track of the state of each bike, e.g. whether it is in stock, hired out or being repaired

- R11: provide the means to record extra details about specialist bikes.

The candidate objects that result from this exercise are:

- list of bikes

- details of bikes" bike number, type, size, make, model, daily charge rate, deposit

- Wheels system

- record of customers

- past hire transactions

- bike

- number of days

- details of a hire transaction: start date, estimated duration

- customer

- receipt

- different amounts of time

- return of a bike

- total amount due

- state of each bike

- extra details about specialist bikes.

We now examine the list of candidate objects and reject those that are unsuitable. Objects should be rejected if they are:

- Attributes: Sometimes it is clear that a noun is an attribute of an object rather than an object itself. Bike number, type, size, make, model, daily charge rate and deposit are clearly attributes of a bike object rather than objects in their own right. Similarly, hire transaction sounds like a possible object, with start date and estimated duration as its attributes. Number of days also sounds like an attribute as do different amounts of time, total amount due and extra details about specialist bikes. Specialist bike, however, sounds like an object. If in doubt ask yourself whether the noun you are considering would be likely to have attributes of its own. Would it have behaviour?

- Redundant: Sometimes the same concept appears in the text in different guises. Here past hire transactions and hire transaction are probably the same thing. Different amounts of time, number of days and estimated duration are probably the same thing - all three refer to the length of a hire (in any case they are attributes, not objects).

- Too vague: If we don't know exactly what is meant by a term it is unlikely to make a good class. For this reason we reject return of a bike as an object. Return of bike is really an event and features in our use case model. Any data we might need to store about bike returns (e.g. date of return) can probably be bundled with the data about hires.

- Too tied up with physical inputs and outputs: This refers to something that exists in the real world but is a product of the system or data input to the system and not an object in its own right. For example, a bill exists in the real world, but is something the system outputs from data it already stores and as such would not be modelled as a class. Receipt qualifies for rejection under this heading. Receipt is an output; it is also redundant as we either store or can calculate the details we would print on it. List of bikes also requires some consideration. If we have an object to represent each bike, we can use these objects to produce a list. Bike, therefore, is a good candidate object, but we can drop the list at this stage. The same applies to record of customers and customer.

- Associations: In the class diagram in Figure 5.1 hires is modelled as an association between Customer and Bike. Whether hires is an object or an association raises some interesting issues and we will postpone that decision until later. The general rule in this situation is that if there is data associated with the relationship (and in this case there is), then we probably want to model it as an object.

- Outside the scope of the system: In this category would be anything we have decided to be beyond the system boundary. For example, according to the Problem Definition in Chapter 2 the system will not cover payroll, personnel or general accounting.

- Really an operation or event: This criterion is quite confusing and should be treated with care. If a candidate object seems to have no data associated with it, then it might be better modelled as an operation on another class. Quite often, however, operations and events are modelled as objects. For example, hiring a bike might be described as an event but as there is associated data, start date and number of days, we are more likely to want to model it as an object (see below).

- Represent the whole system: It is not normally a good idea to have an object that represents the whole system; we want to divide the system into separate objects. Wheels system should be rejected for this reason.

That leaves us with the candidate objects:

- bike

- customer

- hire transaction

- specialist bikes

We can use these objects to form the basis of our class diagram (remember that class names are always singular):

CRC cards

eRe (class-responsibility-collaboration) cards are not officially part of the UML, but are regarded as a valuable technique that works extremely well with it.

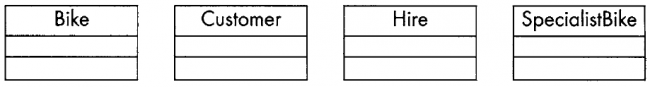

The aim of the CRC card technique is to divide the overall functionality of the system into responsibilities which are then allocated to the most appropriate classes.Once we know the responsibilities of a class, we can see whether it can fulfil them on its own, or whether it will need to collaborate with other classes to do this.

On the front of the card is a high-level description of the class, and the back of the card records the class name, responsibilities and collaborations (if any). An example of a CRC card for the Customer class in the Wheels system is shown in the following Figure. We can see from the figure that the Customer class has two responsibilities; it is able to carry out the first of these (Provide customer information) on its own, but in order to carry out the second responsibility (Keep track of hire transactions) it will have to collaborate with the Hire class.

Software developers find that the simplicity of CRC cards, their lack of detail, make them an ideal tool for exploring alternative ways of dividing responsibilities between classes. It's easy to scrap one design and start again without agonizing about the amount of work that is being discarded. Another way of exploring alternatives is to use sequence diagrams, which are discussed later in this chapter. In practice, however, sequence diagrams show too much detail and are too slow to draw to be useful for this purpose. They are much more useful for documenting the detail of design decisions once these have been reached using CRCs.

This size of card (1ocm x 15cm) is used rather than a sheet of A4 paper to encourage system developers to restrict the size of each class in terms of the number of its responsibilities. Good object-oriented design depends on having small cohesive classes, each of which has limited, but well-defined functionality. The CRC card also encourages developers to specify responsibilities at a high level rather than write lots of low-level operations. The general rule is that no class should have more than three or four responsibilities.

Interaction diagrams

We have already mentioned in Chapter 4 that objects collaborate to achieve the functionality required of them by sending messages. Interaction diagrams model the messaging between a collaboration of objects that will take place in the execution of a specific scenario.

By the time we come to do the interaction diagrams we have already done a lot of analysis: we know what the system has to do, we know about the classes and attributes, and we have had our first real ideas about the nature of the relationships between classesthey have to be able to support the collaborations between objects that we specified in the CRC analysis.

Sequence diagrams

When students who are new to object-oriented technology, especially those who have been trained in procedural methods, first meet object-oriented code, they are staggered by the way the flow of control jumps about on the page. In procedural programming, the sequence of execution proceeds in an orderly fashion from the top of a page of code to the bottom, with only the odd jump off to a procedure. Quite the opposite happens in the execution of an objectoriented program; the sequence of control jumps from object to object in an apparently random manner. This is because, while the code is structured into classes, the sequence of events is dictated by the use case scenarios. Even for those experienced in object technology, it is very hard to follow the overall flow of control in object-oriented code. Programmers, maintainers and developers need a route map to guide them; this is provided by the sequence diagram.

Sequence diagrams show clearly and simply the flow of control between objects required to execute a scenario. A scenario outlines the sequence of steps in one instance of a use case from the user's side of the computer screen, a sequence diagram shows how these steps translate into messaging between objects on the computer's side of the screen.